In 2018, Dr. Vladimir Zelenko published an autobiographical book Metamorphosis, in which he talks about how he, being a completely non-religious young man, came to faith, and how he overcame a serious illness. The book has multiple positive reviews online and was well received by the readers all around the world.

Today, we are publishing the first and the second chapters of the book.

§1

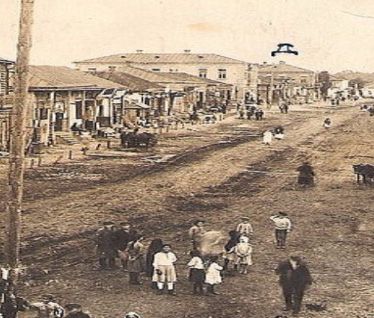

LEAVING RUSSIA

Throughout history, there have been movements that have attempted to deny G-d’s existence. One recent example is the former Soviet Union. To consolidate political power, the few of the ruling class instituted policies that made “THE STATE” of prime importance. Individual freedoms as well as religious observance were viewed as a direct threat to the “almighty” state. Belief in G-d weakened the grip of the tyrannical state by giving people hope and faith for redemption.

For millions of Jews throughout the majority of the twentieth century, the Soviet system was a spiritual hellhole. The Soviet machine chewed up and destroyed lives for the greater good of the state. Jewish observance was illegal and countless Jews were persecuted, imprisoned, and executed.

I was born in 1973 into this perverse society. My young Jewish parents, Alex (Aaron) and Larisa (Leah), had been educated in the Soviet system, and religious life was foreign to them. They only vaguely remembered their grandparents keeping any Jewish rituals and traditions.

My father remembers seeing matzos on Passover at his grandparents house. My mother remembers her grandparents koshering meat and lighting Chanukah candles. Her paternal grandfather used to pray with a minyan [1] every day. The minyan was never held at the same place twice, to avoid detection by the authorities. These vague memories serve as a painful reminder of an interruption of two thousand years of connection between G-d and His people. My four grandparents all came from religious Оrthodox Jewish families and were the first generation to fall victim to Soviet G-dlessness. Stalin’s murderous regime attempted to snuff out all Jewish observance. They closed Jewish elementary schools, yeshivot [2], mikvaot[3], and synagogues.

In addition, the NKVD[4] would spy on, harass, and arrest Jews for trying to maintain their faith. In 1927, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn (the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe), was arrested and imprisoned in the Bolshoi Dom (“Big House”) Prison in Leningrad[5]. The Yevsektsiya, which was the Jewish affairs section of the NKVD, run by Jews, was responsible for his arrest. He was accused of counterrevolutionary activities and sentenced to death.

During one of his interrogations by an atheistic Communist Jew, a gun was taken out and pointed at the Rebbe’s head. The interrogator said, “This toy has made many people talk.” The Rebbe answered calmly, “Perhaps someone who has one world and many gods, but for a person who has two worlds and one G-d, it does not work.”

After incredible international pressure, the Rebbe’s sentence was miraculously commuted and he was released. Shortly afterward, he left Russia. World War II was another event that destabilized Jewish observance. Many Jewish communities were murdered and completely wiped off the map by the Nazis. Large numbers of Jewish families were uprooted and separated from each other, never to be reunited again. The remaining underground Jewish infrastructure was further disrupted.

The quorum of ten Jewish males (in Orthodox tradition) needed to perform certain communal prayers or rites. ↩︎

yeshivah (pl.: yeshivot): Jewish schools for study of the Torah and Talmud. ↩︎

mikveh (pl.: mikvaot): Bathing pool or body of water that fulfills biblical specifications, used for spiritual purification. ↩︎

NKVD: The USSR’s police and secret police agency, precursors of the KGB. ↩︎

Under most of the Soviet regime, the city of St. Petersburg was called Leningrad. ↩︎

An untold number of Jewish soldiers were drafted and killed at the front. All these terrible events made Jewish observance nearly impossible. My paternal grandfaher, Yitzchok, was the youngest of eleven children. He was a soldier during World War II. His job was to build pontoon bridges so that tanks and soldiers could cross rivers. I remember his stories about being bombed and shot at by German planes while he was in the water, building bridges. After the war, he returned to Kiev and married my grandmother. His only two brothers were killed at the front.

My paternal grandmother, Ida, was one of two children. As the Nazis approached Kiev in September 1941, many people started to escape. Her family consisted of her parents, a brother, and her maternal grandmother. Her father, Vladimir (Wolf), was drafted and killed during the war. (I was named after him: “Zev” is the Hebrew equivalent of “Wolf.”) My great-grandmother refused to leave her sick, elderly mother. My grandmother’s brother also refused to leave his mother. As a result, only my grandmother was evacuated from Kiev to Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Whoever remained in Kiev was murdered by the Nazis at Babi Yar, a ravine on the outskirts of Kiev, where the Nazis shot or buried alive more than one hundred thousand Jews.

My maternal grandmother, Esther, was one of two children. Her father, Yehuda, was drafted into the Russian army and he survived the war. My grandmother; her sister, Devorah; and her mother, Riva, were evacuated from Kiev to Fergana, Uzbekistan. Yehuda’s parents were Falik and Hisya Kanievsky from Malyn, Ukraine. They were deeply religious people. Falik died in Uzbekistan in 1943. Malyn was a town next to Zhitomir and a center for the Chernobyl Chassidic dynasty. Those who survived were reunited in Kiev after the war.

My maternal grandfather, Shmuel Nosson, was drafted into the Russian army. During World War II, his army division was surrounded and cut off from the main army. He was trapped in occupied Nazi territory. He joined the partisans and was involved in guerilla warfare and sabotage against the Nazis. He was eventually reunited with the main Russian army and survived. His family was from a town called Romanov, Ukraine. They were evacuated to somewhere in Uzbekistan. He had a younger brother, Lev, who was killed at the front. My grandfather was reunited with his parents in Kiev after the war.

While growing up, my parents experienced anti-Semitism. For example, my mother was told not to even try to apply to Kiev University because she was Jewish. She had to move to Leningrad to go to school. My father was called Zhid, a deroga- tory term used for Jew, throughout his childhood and schooling. He broke a few people’s noses in defense of being Jewish. He told me once that he did not know what it meant to be a Jew, but he could not tolerate anti-Jewish sentiment. I used to attend day care. One time, my grandmother came to pick me up and overheard the caretakers calling me “that little Zhid.”

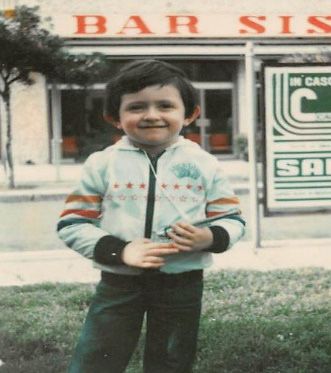

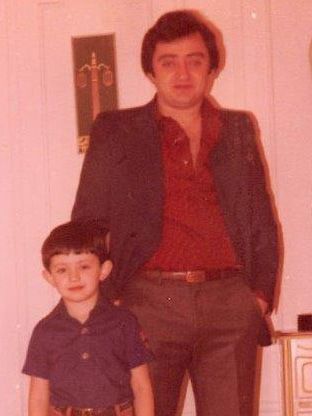

My father grew increasingly disillusioned with life in the Soviet Union and decided to move to America. Initially, my mother was against the idea of moving because she did not want to leave her family behind, but eventually she consented. In 1977, when I was three years old, my parents and I left the Soviet Union.

We left Kiev by train. My entire extended family was at the train station to say goodbye. My grandparents were not interested in leaving Russia in their old age. My mother told me that she thought it would be the last time in her life that she would see her parents.

As the train pulled away from the station, I waved to everyone while crying. My grandfather, Shmuel Nosson, looked at his wife and then at me, and suddenly said, “We are moving to America.” He then explained, “He cannot live without being close to me.”

In 1979, my four grandparents left Russia and moved to New York. They settled in the same apartment building that we were living in. In 1980, the immigration window closed, and the rest of my extended family members were unable to leave. They remained stranded in Russia until 1991, when the Soviet Union began to fall apart.

§2

COMING TO AMERICA

We left Kiev and arrived in Vienna, Austria. After staying there for ten days, we were given permission to take a train to Rome, Italy. We lived in Rome awaiting permission to come to America.

After three months, we received visas, immigrated to New York, and settled in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn. My parents came to this new country in pursuit of a better life. What did a better life mean for a young immigrant family from the USSR in 1978? For the typical immigrant, it meant the pursuit of materialism and the avoidance of anti-Semitism.

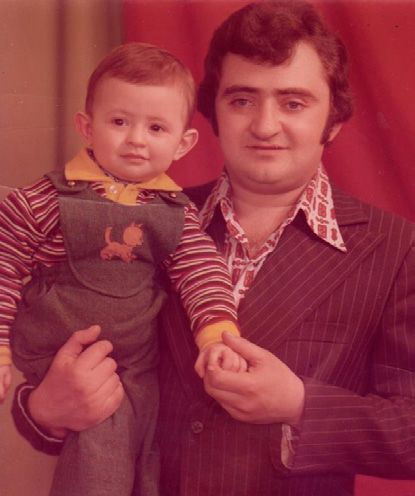

A few months after arriving in U.S., my father took me to an organization called F.R.E.E (Friends of Refugees of Eastern Europe) in Crown Heights, and they organized my circumcision. I remember my circumcision. I recently asked my father why he did it. He told me that when he was eight days old his grandfather had him circumcised.

My father became a taxi driver in New York City, my mother worked in a fur coat factory, and I was enrolled in public school. One time when my father was working in Manhattan, he was pulled over by the police. When the officer came over, my father offered him twenty dollars. The officer laughed and said, “This is not the old country; please don’t bribe the police here.” He let him go with only a warning. Throughout my childhood, my father worked sixteen-hour days driving his taxi. It was grueling work and I was impressed by his work ethic.

While working in the fur factory, my mother took computer programming courses. When she graduated, she got a job at The Home Insurance Company and worked there for over ten years until the company closed. Afterward, she found a good job working for Morgan Stanley. She worked there for many years until she got sick. During my childhood, my mother was a real superwoman who was able to balance her work life with her family responsibilities. I owe my parents a great debt of gratitude. They taught me that a person could only succeed through consistent hard work. I learned from an early age that I would need to combine raw intelligence with steadfastness. Only then would I get myself out of the “ghetto.”

When I was seven years old, my brother Frank (Ephraim) was born. He had his bris[1] on the eighth day after his birth, as is customary in most countries where all are free to practice their religion. As I will explain later, Ephraim was inherently spiritual and connected to G-d from the very beginning of his life. As my spiritual journey evolved, Ephraim was always surprisingly supportive of me. He believed in G-d, the soul, and spirituality many years before I even started to think about it.

bris (pl.: brisim), short for brit milah (lit., “covenant of circumcision”): The Torah custom (Genesis 17:10–14) of circumcising Jewish males, usually on the eighth day after birth. For most Jewish Soviet émigrés, it was only upon leaving the USSR that they were finally free to undergo brit milah and adopt other religious practices. ↩︎